Collaboration outweighs competition for research in Maryland

Published 11/30/17 in the Baltimore Business Journal

Despite working for two universities long considered rivals in academic and medical research, professors Michael Matunis and Alex Drohat have found they can achieve more by working together rather than competing for funding and recognition in their fields.

Matunis, from Johns Hopkins University, and Drohat, from University of Maryland, Baltimore, met at a conference in Baltimore in 2011 and quickly realized their overlapping research interests.

The next year, the pair secured a three-year, $350,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health to support their collaborative research around the behavior of specific proteins in the human body. They have since secured an additional three years of funding.

Their work represents a larger trend seen in recent years of universities teaming up on research projects. Institutions in Maryland are finding more opportunities to join forces. It’s a shift that has allowed researchers to expand beyond their individual capabilities, and the specialties of their schools. Additionally, collaborative projects bring more federal funding to Maryland universities and produce more economic opportunities for the state overall.

In the case of Matunis and Drohat, the pair’s complementary expertise brought more breadth and value to their work. And their proximity, both working at universities in Baltimore, made the collaboration even more opportune, Matunis said.

“He does more biochemistry and biophysical-type experiments and I’m more of a cell biologist,” he said. “The fact is, we can do experiments together that we couldn’t do individually.”

To move quality research forward, investigators need the best tools, the best partners and, of course, funding. Joining forces across institutional lines is how many are bringing all of that together.

The fight for funding

Matunis said a key reason for the uptick in collaborative ventures is the increased difficulty of getting projects funded.

“I’ve had funding for my lab for almost 20 years,” he said. “But things have gotten more competitive, and recently, funding has remained pretty flat, which is a decline in relative dollars as everything else involved in the research gets more expensive.”

Helen Montag, senior director of business development and corporate partnerships at Hopkins, said federal and private grant funding is “harder than ever” to get. Additionally, organizations like National Institutes of Health, which doles out billions in federal research grants annually, are incentivizing more cross-disciplinary work.

Johns Hopkins has ranked first among U.S. universities in research and development spending for the past 37 years. The institution also tops the National Science Foundation’s list for research expenditures paid for with federal dollars, spending about $2 billion in federal money on projects in 2015. But even at a school with a powerhouse reputation, researchers often find it is easier to get funding when they reach beyond the walls of their own institution.

For instance, Hopkins is working with University of Maryland, College Park on research efforts around big data, thanks to a $30 million grant from the state.

Montag said in many cases, creating partnerships makes more sense than trying to duplicate strengths that already exist in the state. Hopkins, for example, doesn’t want to build an adult shock trauma operation because the University of Maryland already has a successful one.

Even smaller institutions, like Morgan State University, have been ramping up collaborative research efforts and bringing their specific areas of expertise to the table. In environmental science, Morgan State’s Professor Chunlei Fan is working with peers at University of Maryland Eastern Shore to research climate variability and its influence on Maryland coastal bay ecosystems. The project is backed by a $23,000 grant.

“With these kinds of collaborations, we can tap into the talent we have all over the state, and build on the competencies that each of our universities have,” said Victor McCrary, vice president for research and economic development at Morgan State. “We have a major university network in the state, full of talented people. We need to find a way to build on all of that, bring those elements together to do the best good.”

A ‘team sport’

Laurie Locascio, University of Maryland, College Park’s new vice president for research, said research is becoming “more of a team sport” among universities across the nation. If Maryland can put forward the best collaborative teams, it could bolster its efforts.

“It makes us more competitive nationally when we combine forces, rather than working in a vacuum,” Locascio said. College Park has multiple ongoing partnerships that were funded at $27 million in fiscal year 2017.

Many schools collaborate on a project-by-project basis, but two of the state’s largest research institutions are being very deliberate about promoting intra-university cooperation. A partnership between University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore, officially known as “MPowering the State,” was launched in 2012 with the intent of growing collaborations among the two campuses. The initiative includes joint faculty appointees, shared resources and cross-disciplinary research facilities, like the Center for Sports Medicine, Health and Human Performance — a program set to be housed in College Park’s redesigned $155 million Cole Field House.

University of Maryland President Wallace Loh has said the initiative began as a melding of the minds between him and UMB’s President Jay Perman. It has since become law. The universities have put about $10 million behind the MPower initiative, Loh said, and that investment has already yielded returns of about $120 million in research funding support.

Inventions developed at the universities have also grown from about 80 to 331 since MPower’s inception, and dozens of startup companies have been built around the research and technology being licensed out of the schools.

Dr. Bruce Jarrell, chief academic and research officer at University of Maryland, Baltimore said the two campuses have almost no crossover in expertise.

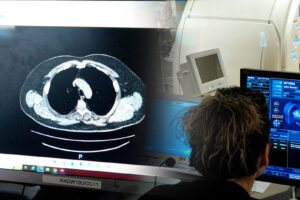

The Baltimore campus specializes in dentistry, medicine, social work, law, nursing and pharmacy, while College Park excels in areas like math, science, cybersecurity, education and public policy. Some of the cross-disciplinary partnerships that have formed focus on integrating virtual reality technology with shock trauma training, creating educational programming for police around implicit bias and tracking and addressing human trafficking in Maryland.

Jarrell said he hopes MPower can serve as an example of how powerful institutional partnerships can be within a university system. The program is still young, but he expects it to grow, and continue to bring in major funding returns in years to come.

“All of these individual projects are valuable,” Jarrell said. “But we also can’t forget about the broader impact, on our students and our state: how we are helping to improve things for future generations.”

For the greater good

Montag, of Johns Hopkins, said ultimately all Maryland universities have aligning goals: to continue creating new knowledge and capabilities, to help boost the state’s economy and to solve some of the world’s most important problems. With the same goals, it makes sense they’d work together to achieve them, she said.

“I’ve been almost 20 years, and there wasn’t always this cordial relationship among us, but I think that’s really changed,” she said. “I think we’re really getting behind the idea that rising tides lift all boats.”

Research is a major economic driver, said Locascio, the College Park research head. It’s resulting in new technologies, companies and job opportunities. Building more partnerships among in-state universities could ensure those benefits, she said, and all of the funding and recognition that come with successful research remain in Maryland.

Karl Steiner, vice president for research at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, said institutional collaborations could also help the state become a leader in solving the biggest “problems of today.” Those problems lend themselves to a more interdisciplinary approach. It’s no longer enough to get a handful people together from the same place, with the same expertise to solve some singular problem, Steiner said.

“Major national and international priorities like cybersecurity, discoveries in biotechnology, managing sea level rise, those are things that can’t be handled by one university team,” Steiner said.

Solutions to those problems are going to involve public policy, health, law, engineering and bioscience, he said. No one institution can meet the demands alone.

“It’s much better for us, as institutions, and us as Marylanders to say ‘Let’s do this together, and keep the impact in Maryland,’” Steiner said.